Developing Ringing Skills

Introduction

We have seen in the beginners guide (http://chiltern.odg.org.uk/Training/BeginnersGuide.html) the basic elements of becoming a bell ringer. In this section we aim to provide some guidance on the often confusing terms used and some tools to help with home learning. We also provide some ideas about how different teaching and learning ideas may help, hinder or delay progress. Whilst we are all individuals with our own ideas of how we learn best and how we feel most comfortable within our ringing the author hopes that we can all understand that if we wish to ring at the highest levels such as the national 12 bell striking competition (link to web http://www.12bell.org.uk/) then the techniques used by these highly experienced ringers may be more appropriate than local home spun myths and legends about how to advance. The aspiring ringer is therefore encouraged to visit these and other ringing sites to obtain tips and help. You will also find various links to guides within this document although as many of the sites referred to are maintained by volunteers within local associations or towers we can not be assured that the links will always work and sometimes recourse to search engines will be required.

The concept of Place

The Beginners Guide introduces the concept of how a bell may move relative to the other bells within the sequence. It also introduces the concept of place which is simply a term used to show whether the bell is first, second, third, etc. within the sequence. By convention the first place will be occupied by the highest pitched bell note (treble) and the final place by the lowest pitched (tenor) when the bells start ringing in rounds. Movements from this simple sequence will occur when the conductor tells everybody to start a method.

You will also recall that each bell rings once in each sequence and that the objective of methods is to allow all possible sequences to be rung. For practical reasons bells are not permitted to “jump” from one end of the sequence to the other or to miss out any opportunity to ring so each and every bell will have a pull within each sequence. In practice bells are only allowed to stay in their place within the sequence or to move one place back or forward at each stroke. Even when only moving one place the ringer may need significant skill to ensure they strike the bell cleanly amongst the others.

Taking the example of a typical 6 bell tower with one bell always last in the sequence (tenor covering behind the others) there are 5 other bells between each stroke of a bell ringing rounds.

When two bells swap places within the sequence one will move forward a place whilst the other moves back. In practical terms to move forward the ringer will need to ring more quickly whilst the ringer of the other bell rings more slowly to let them move forward in the sequence. If we count the number of other bells sounding between two strokes of the moving bells we will realise that the bell moving forward (towards leading the sequence) only has 4 other bells sounding between its successive strokes. (The bell it swaps with will not be heard between its two strokes). Meanwhile the bell moving back in the sequence will have 6 other bells sounding between its strokes. (The bell it has swapped with will sound twice between these strokes)

This is shown below as seen by bell number 4 in the sequence swapping place with bell number 5

Rounds 1,2,3,4,5,6. 1,2,3,4,5,6. | Moving in a place 1,2,3,4,5,6 1,2,4,3,5,6 | Moving out a place 1,2,3,4,5,6 1,2,3,5,4,6 |

To achieve these movements the ringer needs to accelerate the bell by approximately 16% relative to normal rounds speed to move forward one place or to slow by 16% to move back a place.

Obviously when more bells are involved the changes of pace are less (10 bells 10% change of speed) and easier for the ringer to achieve whilst with fewer bells the changes are greater (4 bells 25%) requiring greater effort and skill from the ringer. We will see later how these differences in speed are only required for a single stroke within call changes but that the ringer may need to ring several stokes steadily at a faster or slower speed than rounds when moving between the ends of the sequence as happens within methods.

The Blue Line

This is the term adopted by ringers to describe the path their bell takes amongst the other bells in a method. Whilst commonly the path is shown as a blue line for a working bell (one which follows the method) and often as a red line for the treble bell the important thing is the pattern of the line not its colour. You will find that the tools referenced from this page often have additional colours so the learner can select other bells to see clearly how their “blue lines” interact with their own.

Fortunately we live in an internet age where there are many on-line resources which the aspiring ringer can access to assist in home learning. Most will have some sort of blue line to show the movement of the bells but there are a number of alternative presentations which some may prefer. Many experienced ringers also use other techniques to remember the pattern of movements their bell needs to follow (rather than memorising a blue line). The more observant may have noticed some of these displayed on Peal Boards in towers where a series of numbers and sometimes crosses are used to define a method. This note is not intended as an explanation of such advanced techniques. They are simply mentioned to demonstrate that when advancing to long and complex methods most ringers need memory prompts and a basic understanding of method construction and could not cope with trying to learn a long string of numbers (bells to follow) or even just blue lines.

It is also worth noting that many ringers will first be introduced to methods as a series of pieces of work which break up the simple pattern of plain hunting between the ends of the sequence. This often results in the new ringer knowing the method but not necessarily where each bell starts its work on the line. Depending on the ringer’s personal learning style they may well spot the symmetry within many methods and have the capacity for only learning a part of the line and then ringing it forwards or backwards as appropriate. Unfortunately such shorthand learning techniques don’t teach any concept of place bells, an understanding of which can be very helpful as ones ringing progresses. Rather than repeat what is widely available on the internet the reader is urged to refer to https://cccbr.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/200709.pdf which is just one of many very helpful articles available from the Central Council of Church Bell Ringers. Search engines will quickly find these if the link doesn’t work.

Many of the best ringers will actually spend considerable time home learning, possibly even more than actually ringing, to ensure they can give the best possible performance when in the tower. Whilst ringers are generally very generous with their time and assistance to learners it is worth remembering that like any team activity the failure of any member to properly prepare for a performance is a waste of the other member’s time.

Learning by Place or Numbers

When starting to ring methods, learners usually want to adopt a simple approach and try to memorise the numbers of the bells they will be following. Unfortunately this is only a very short term expedient as each bell has a different sequence of numbers to follow and with even simple methods often having over 100 sequences it quickly becomes impractical to remember them all. The learner who attempts to memorise all of the bells to follow may, however, notice repeating sequences of numbers but possibly with one or more bells coming at seemingly random points within the sequence and thus avoid learning them all.

Experienced ringers therefore will always frustrate the newcomer by saying don’t learn the numbers. This isn’t due to some malevolence on their part but a very real recognition that to make progress, place is of much greater value. It also often reflects their own learning journey where having grasped the concept they realised how much time they had wasted trying other ideas first.

Simply knowing the number of a bell to follow tells the ringer nothing about how they are moving within the sequences and is totally unhelpful if the bell you expect to follow is in the wrong place or the conductor changes the sequence of the bells with calls.

At first ringing by place may seem impossible, however, time spent mastering the concept using tools on this or other websites will greatly speed progress, satisfaction and accuracy of ringing. To give a few examples:

I should follow the 3 - if they are wrong you will be. If, however, you are thinking I’m in third’s place having any two ropes ahead of you will mean you are in the correct place within the sequence.

I follow the 3 and then the 5 - this provides no idea as to whether you should be going slower faster or maintaining rounds speed. If you are thinking I’m going from 4ths place to 5ths place it tells you to ring slower. Similarly 5ths place followed by 5ths place would be rounds speed and 5ths to 4ths speeding up.

Initially the new recruit may start with one of the simplest ways of changing the bell sequences, known as Plain Hunt, the bells simply swap places with their neighbours and continue doing so until everybody has been to the front and back of the sequence. To avoid the sequence instantly returning to what it was before the first or leading bell will actually stay in place for two blows and this simple approach will only generate twice the number of sequences as the number of bells (5 bells 10 sequences).

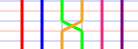

This diagram shows Plain Hunt doubles The bells change places in pairs from the left of the diagram unless a bell has just reached the front (left) or the back (right) when it will remain in place for one more stroke. If a bell stays in place, the higher placed bells change place in pairs. |

To obtain more sequences we need to complicate things by causing other bells to ring 2 or more strokes in the same place which may in turn force other bells to alternate their place with a neighbour in something known to ringers as a dodge (because the bells involve dodge around each other trying to avoid a clash). It is these two common actions (making a place or a dodge) around which all ringing patterns are developed. There are of course many variations of these actions where multiple places or dodges may be made. It will hopefully be appreciated that it is impractical to remember numbers for all such actions whereas place gives a simple and easy point of reference.

As one advances with ringing you will also find the concept of place and what individual bells do being described by something known as place notation a good explanation of which can be found at http://www.cccbr.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/200404.pdf.

Useful numbers

The new ringer will generally be starting with methods where the construction has a clear pattern to the order in which the bells lead. This is known as course order and each bell has a course bell which is the one following it to lead and also a before bell which it takes from the lead.. Each bell will remain sandwiched between these until the conductor makes a call (bob, single etc,) and they provide a great deal of help in establishing that one remains in the correct place. Knowing the number of ones course bell and before bell will help a great deal in providing confirmation that one remains in the right place. In many of the more commonly rung methods their symmetry is also such that you may always do pieces of work with particular bells again knowing the number of such bells can help.

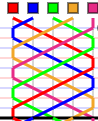

The yellow bell is the ‘course’ bell to the blue bell The blue bell is the ‘before’ bell to the yellow bell See also : “Turns you” in the Common Terms section |

Many ringers also make use of other visual clues within the pattern of ringing most commonly in respect of where they pass the treble bell as explained in. https://cccbr.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/199910.pdf

It is far easier and less taxing on the brain to research the various shortcuts than to try remembering long sequences of numbers. People have been ringing for centuries and have fortunately developed these techniques and published them to help us.

Standing behind (receiving and giving advice)

Like many things it is often easier to watch others and follow their actions as a means of learning a new skill. Within bell ringing there are sometimes more ringers than bells and those ringing the bells may be ringing methods of which we have only limited knowledge. This presents two opportunities to the novice; one is to sit or stand at the side feeling annoyed at not being asked to ring a bell, the other is to politely ask if it is possible to stand with one of the ringers and to try and observe where they are ringing. Obviously to be of real benefit the learner will need to have some concept of what the person being observed is attempting to do and this requires homework by the learner possibly using tools found further on within this section of the website. As is often heard, however, other tools are available and a keen learner will use a wide range of resources to help them understand the theory of ringing which most experienced ringers will tell you is a great help when trying to learn new methods as it provides easily remembered prompts.

Common Terms

Having done some homework and hopefully had opportunities to observe a method being rung it will be time to try it oneself. At this stage you may be lucky to have an experienced ringer stand with you to offer help and advice. Unfortunately this can be where problems arise as the advice may not be in forms you find helpful. The issue almost certainly being with jargon, the timing of the advice or its format. Thus it is helpful if the learner and advisor take a few moments to agree what is required and that both parties understand the terms being used. Whilst some terms such as lead may be fairly universal and easily understood others seem to cause difficulty. We have attempted to give some common terms below but like any good learning tool this website can be added to and amended so please feel free to tell the webmaster of potential improvements.

Holding up, ring slower

When moving backwards within the sequence of places it is necessary for the ringer to slow their bell relative to the other bells and the pace of normal rounds. This is achieved by allowing the bell to rise further in its swing possibly almost standing it (remember the bells swings full circle and the higher it swings the longer it takes to swing back) thus this possibly confusing term has a logical explanation describing the bell’s action.

Pulling in, ring quicker

For the bell to make its next stroke more quickly when it moves forward in the sequence the ringer will need to check its upward swing and then pull harder (hence pulling in) so it can return to its normal swing point.

Dodge up

By convention the start of the sequence is thought of as the front and the end of the sequence as the back hence you will hear terms such as front bells for the ones nearest the treble and back bells for those nearest the tenor. It is also normal to think of moving from the front of the change to the back as going up (logically this fits with the idea of allowing the bell to swing further up to slow it down) so a dodge or other type of work when moving from the front of a sequence to the back is known as an up dodge usually also specifying the place where it occurs. For example 3 / 4 up. It should be noted that a dodge will involve the ringer dramatically changing the speed of the bell in successive strokes as instead of progressively moving through the places in the sequence with a number of successive slower or quicker (than rounds speed) strokes they will be reversing direction for one stroke before continuing.

Dodge down

A dodge whilst moving from the back to the front of the sequence.

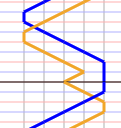

The blue line is performing an ‘Up’ dodge, The mauve line a ‘Down’ dodge |

Make place(s)

This is the term for staying in a place within the sequence. This means ringing at the normal rounds speed. The term is further complicated and clarified by additional terms such as “long” if the places are being made for more than 2 blows.

Snap

No not a card game or an invitation to clash with a neighbouring bell but a simple term to show that one is only in a particular place for a single blow. Hence snapping into and out of the place very quickly.

This extract from Stedman doubles illustrates the mauve line performing a Snap at lead and the blue line snapping into second place before returning to lead. The essential difference from a dodge being that with snaps (sometimes also known as points) the bell reverses its direction of hunting whereas at a dodge, the bell resumes hunting in the direction it was going. |

Turns you

Oh dear maybe some more confusion but by convention a term meaning the bell which replaces you at the end of a sequence. The logic here seems to be that when you reach the end of a sequence by being the last or first bell you have to turn away from that position and go back the way you came so the bell entering the position in the sequence you left has turned you.

|

Shorthand

Due to the vast number of permutations and sequences which can be rung methods can be extremely long and contain complex wiggly blue lines indicating the path of a specific bell. The ringer will therefore encounter many examples of people using shorthand descriptions of sections of line. These need not concern the beginner but are very useful as over time one’s brain becomes cluttered with multiple methods, at which point terms such as Yorkshire Places, Stedman front work etc.etc. start to provide shorthand clues to what is required.

This note is not intended to cover the many hundreds of ringing terms which are in common use and those seeking more complete explanations are encouraged to refer to Web based glossaries such as http://www.jaharrison.me.uk/Ringing/Glossary/A.html#top

Ropesight (and covering behind)

This is arguably the most difficult thing to explain but never-the-less a key skill which we all aspire to. Again it may be most easily mastered when not actually ringing a bell but rather through careful observation. The new ringer will inevitably have much to learn and assimilate and will initially be using a significant part of their cognitive ability to simply handle the bell and worry about whether they are letting the team down, striking in the wrong place etc. By watching others ring (even on Youtube) it is possible to train the eyes to see the sequences in which the ropes fall. Initially this may be easiest by watching a method where the tenor is always the last bell and just trying to see which ropes the tenor follows. There will be a pattern to this as obviously the method will define which bell strikes last but one (tenor will always be last) and a knowledge of the method may help with spotting but the real skill is actually just training the eyes to scan the ropes and gain an idea of which is last.

Although many people will say covering a method behind is easy because you don’t necessarily need to know the method and just have to ring at a steady pace you still need to be the last bell so don’t ever miss opportunities to cover behind they are good for developing listening skills (usually easy to hear the deepest note) and ropesight (spotting the last rope) without the difficulty of also having to change the position of ones bell and remember a method.

Tools to help you

Method Tutor http://chiltern.odg.org.uk/Methods/MethodTutor.html

This allows you to test your knowledge of a method by selecting a method from the library and then ringing it with the arrow keys. A useful self check that you know the blue line before visiting the tower.

Method Diagrams http://chiltern.odg.org.uk/Methods/MethodDiagrams.html

A source of many common method blue lines

Variations Cross reference http://chiltern.odg.org.uk/Methods/VariationsXRef.html

As many of the Chiltern Branch Towers only have 6 bells this table gives a number of variations which demonstrate the wide range of potential methods, the impracticality of learning the number sequences for all of them and provide an opportunity for aspiring bands to ring the changes, as always ringing the same methods is rather boring.

Developing Conducting Skills

So far we have dealt with learning to handle a bell and ringing a method. There is, however, another important component which is finding somebody to conduct. Ideally all ringers would develop a knowledge of conducting partly to ensure there was always someone present willing and able to conduct but more importantly as the homework involved in seeing how to conduct greatly reinforces one’s own knowledge of a method. Many conductors actually start in the role not through particular knowledge or skill but out of a desire to help their band ring something more interesting than plain courses. This article from North America contains much good advice about getting started in conducting and some of the etiquette involved. https://www.nagcr.org/articles/2015/03/on-conducting.html

There are a few key aspects of conducting where jargon and common standards are required. Conventionally conductors should give two strokes warning of a requirement for a change whether this is a simple call change or an instruction to start a method or make a change within a method. Obviously two strokes warning may be slightly more or less for some bells as the instruction will be given during the ringing and will take longer than the time between two bells striking to deliver. All instructions will normally apply from the following handstroke and in most methods will be made two blows before a lead end which is when the treble finishes its leading. (Note that definitions and understanding of lead ends and lead heads may be poor and the reader is advised to refer to the glossary linked earlier in these notes). Aspiring conductors will need to look carefully at when these two blows of warning should be given as methods such as Grandsire with its extra Hunt bell have the call earlier than Plain Bob and Principles such as Stedman have calls at specific points within the 6’s which form the method.

It is important that conductors take care over the timing of their calls as many ringers rely on the place they are in when the instruction is given to decide what to do next.

Whilst many bands have the idea that their conductor possesses some sort of miraculous skill for correcting mistakes it is obviously better that bands help the conductor by not making mistakes. Whilst a good conductor will be able to spot that bells are in the wrong sequence even if striking perfectly correcting such issues will inevitably disrupt the ringing and may trigger further mistakes.

Whilst there are many possible ways to change basic methods to create full extents of possible sequences generally they are restricted to commonly agreed variations known as singles (which affect the course order of a single pair of bells but may cause all bells to do something different as they are made) and bobs which generally alter the course order of 3 but possibly more bells. Other more specialist calls such as Extremes exist but are less commonly rung.

The following resources are available to help

Touches http://chiltern.odg.org.uk/Methods/Touches/index.html

These are a number of common method touches which conductors will need to learn if wishing to go beyond plain courses

Method Diagrams http://chiltern.odg.org.uk/Methods/MethodDiagrams.html

This tool allows the aspiring conductor to make the calls and see how the impact the blue line. By experimentation it may be possible to identify true touches which are not shown in the Touches table as the tool includes capabilities for identifying falseness where a sequence is repeated before an extent has been rung

Rather than repeating guidance which can be readily found within a number of ringing society webpages the following links are offered for the inspiring conductor to consider. The first to the whiting society will also take the reader to many other excellent bell ringing tips, articles and publications from this group covering all aspects of the hobby. The second is possibly more relevant to the Sunday Band conductor as it includes much detail in support of the touches outlined in the branch link given above.

They will see common themes emerging about the importance of thoroughly learning the compositions to be called and the impracticality of hoping to know what every other ringer is doing whilst simultaneously ringing ones bell and giving instructions at the right time.

https://www.whitingsociety.org.uk/articles/advanced-tuition/notes-on-conducting.html

http://www.cambridgeringing.info/Methods/conducting.htm

Draft compiled by Chris Potter, Branch Training Officer, 24th September 2019 with assistance and help from the Alan Masters, Branch Webmaster who also developed the tools and models and input from various local ringer comments.

If you have any ideas for improving this or the beginners guide notes please email training@chiltern.odg.org.uk or webmaster@chiltern.odg.org.uk